About this episode

Adam Gidwitz (A Tale Dark and Grimm, The Inquisitor's Tale) talks about his journey to finding truth through literature and how he found his voice to tell the truths he's learned.

"The world is so complex, right? No theory that anyone has can be accurate because the only accurate model of the world is the world. There are too many complexities. … And so what literature does is it catalogs the unique and particular truths of the world and a really great writer, a Jane Austin, Chekhov, Kate DiCamillo, will take one of those truths and reveal it to you in a narrative way that's just so deeply satisfying." - Adam Gidwitz

Contents

- Chapter 1 - Writers Don’t Always Write (2:36)

- Chapter 2 - Adam's House (5:10)

- Chapter 3 - Slow and Steady (9:36)

- Chapter 4 - The BFG (12:15)

- Chapter 5 - Not Johnny Tremain (17:10

- Chapter 6 - Discovering Truths (22:06)

- Chapter 7 - Thinkers, Poets, and Monsters (26:39)

- Chapter 8 - I Wish I Was Cast As… (31:37)

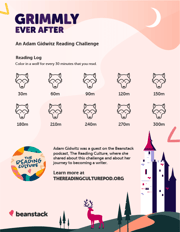

- Chapter 9 - Grimmly Ever After (32:49)

- Chapter 10 - Beanstack Featured Librarian (34:17)

Adam's Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

Adam Gidwitz: The world is so complex. No theory that anyone has can be accurate because the only accurate model of the world is the world, right? There's too many complexities. Everybody is too unique. There's no predictive capability at all. That's why you can't tell the future. What literature does is it catalogs the unique and particular truths of the world, and a really great writer, a Jane Austen, a Chekov, a Kate DiCamillo, will take one of those truths and reveal it to you in a narrative way that's just so deeply satisfying.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: One of the biggest hoodwinks adults pull on us as kids is in making us believe that answers are simple, convincing us that truths are easy to come by and even easier to understand. But ironically, the truth is that that's not true. Universal truth is something that Adam Gidwitz spent a lot of his young adult life searching for. He believed he could find it in lessons of philosophy or religion, but instead he found his way into the endless small truths told through fiction. Adam Gidwitz is a bestselling author known for the Grimm series, as well as his novel, The Inquisitor's Tale, which earned him a Newbery honor. He joins us today to share more about his relationship with fact and fiction. He'll tell us about the trial and error he went through as a writer, finding his own style, and about his upcoming novel, which presents recent history's ultimate evildoers as people whose truths are more complex than we'd like to admit.

Adam Gidwitz: What they did was monstrous, as bad, worse than anything that's ever been done, arguably. But it's important to me that we depict them as humans because we have to understand how humans could do monstrous things.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: He'll also fill us in on what character he was hoping to play in the Netflix adaptation of A Tale Dark and Grimm. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookie, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and reading enthusiasts to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Let's get started with you painting us a picture of Little Adam.

Adam Gidwitz: Little Adam was an idiot. I have a report from second grade from my gym teacher that just says Adam is a space cadet. That's really who I was. In fact, this is very recent now. I've never said this in public, but I'm going to tell you. Pretty recently, my shrink asks me, my psychiatrist, she goes, "So were you diagnosed with ADD as a child?" I was like, "Wait, what? No. Should I have been?" In retrospect, looking back at the way I behaved back then, the answer is obviously I should have been. I would always get these reports from school. If Adam would only pay attention in class, he would be an excellent student. He would be... He's very smart and he would be an excellent student. I was always like, I felt proud of that. I was like, "See, they think I'm smart." I was [laughter] not paying attention to the side where they were like, "But he's not a good student." A lot of things changed as the major events in my life changed my approach to how I live. One of the things that was salient to what I am now is I hated writing.

Adam Gidwitz: I found it very hard. I certainly never thought of myself as a writer. What I did love to do though, and this was less in school and much more privately at home was I spent a ton of time imagining. I had GI Joes and I played with my GI Joes all the time. I was lucky enough to have a basketball hoop on my driveway that could go up to 10 feet or down to four feet. And I thought I was going to be, or I wanted to be a professional basketball player. So I probably should have left it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: You can dunk on them with your short basket.

Adam Gidwitz: Exactly. Exactly. I should have left it up at 10 feet and actually just practice my jump shot. But no, I would definitely just put it down to four feet and just like dunk and narrate these like hour-long, two-hour-long stories between when I got home and when dinner was served. But I never considered that writing. I never thought of it as writing. I remember having an author come to my school when I was in seventh grade and somebody asked her, how do you know if you're a writer? And she said, writers, write, which I think she meant as really empowering.

Adam Gidwitz: Like as long as you're writing, you're a writer. But I wasn't writing. And so I remember very clearly leaving the auditorium in seventh grade after that. And I remember like where I was, like the red seats and I was the red, the banisters and I was coming up the stairs to leave the auditorium and I thought, I am not a writer and I never will be.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: How would you finish that sentence? Writers...

Adam Gidwitz: Writers imagine. And eventually, if they want to get paid, they write it down.

[laughter]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Was your household like a storytelling household? Was it a funny place?

Adam Gidwitz: That's a really good question. You know what? I don't think I've ever been asked that question. I've been doing this job for quite a while now, over a decade. So I appreciate you asking that. And as I think about it, I think it was both a storytelling household and a humorous household, but in like separately. My dad isn't really a storyteller, but he has this sort of moralistic way of delivering anecdotes that have really beautiful arcs and in ways that are very satisfying. And he would often have to speak at fundraising events or whatever. And he would tell stories about how he never wrote his speeches beforehand. He would sort of listen to what was going on around, and then he would sort of prepare a speech in the moment and deliver it, and it always ended with one of those satisfying moments. And so with crafting of that kind of narrative, I must have gotten from him. My mother, on the other hand, is not that kind of storyteller at all, but she's very funny. She's like wickedly funny. And she got it from her mother, my grandmother, who was wickedly funny and mostly just wicked. She was at a really, really very sharp sense of humor.

[laughter]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Emphasis on the wicked.

Adam Gidwitz: Yes. Grandma was just amazing. And being out at like a meal with her was terrifying because you never had any idea what she was going to say to the waiter, but it was usually going to just like crush him and humiliate you forever. But it was right on the money. So between my mother's humor and my dad's sort of sense of narrative, I think that's where...

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Out came you.

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I'm curious, do you have any examples of the types of stories that your dad used to tell?

Adam Gidwitz: I was trying to remember one that he definitely told me. He definitely liked some of the Zen stories. Are you familiar with the Shalom Aleichem short story, If Not Higher?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah.

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah, he's a Yiddish language, I think, Yiddish language writer who took that name. And his, I think, most famous story is called If Not Higher. And it's, again, this kind of story that my dad used to like to tell me. There was a rabbi in a small town in Eastern Europe who was beloved by his congregants. And they said he was so holy that on the High Holy Days, between the services, between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, which are separated by eight days, he would rise up into heaven. And in this town, there was a Litvak, a Lithuanian Jew. And I'm a Lithuanian Jew, so I'm allowed to call him Litvax. But it's a little bit like Litvax always in these stories are a little bit skeptical. And so this Litvak did not believe that the rabbi actually ascended into heaven. And so he determined one year that he would follow the rabbi when he left the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah to see where he really went.

Adam Gidwitz: And so after the services on Rosh Hashanah, the Litvak was waiting out behind the synagogue. And he saw the rabbi emerge. And he saw the rabbi walk into the woods. And so he followed him. And he saw the rabbi walk through the woods for an hour or two until he came to a little hovel. The rabbi went inside and the Litvak waited outside. And when the rabbi came out, he was disguised. He had on woodcutters clothes and an axe and dirt on his face. He was unrecognizable. And the rabbi went and started to chop wood. And he chopped and then he went back to his own village and started to hand out wood to the poor people, the old women and the old folks who couldn't cut their own. And whenever they offered to pay him, he always refused. And he spent eight days doing that. And then he returned for Yom Kippur. And after the services, the Litvak sort of reappeared in town and everyone said, "So did you do it? Did you follow the rabbi? What happens? Does he ascend to heaven?" And the Litvak says, "If not higher." It makes me teary just like it would make my dad teary.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Oh, my gosh. I love that story. It's beautiful. Did you, I'm assuming you also love to read stories growing up and what were some of those stories that you found on your own as a kid?

Adam Gidwitz: As a first grader, I was introduced to Encyclopedia Brown. And I remember that being the first time that I really like fell in love with some with the written word. And I read a bunch of those. And those actually, I just, we're going to talk about my dad the whole time. What a surprise. My shrink would be jealous.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah, you can just pay me after this.

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah. Okay, cool. Like my dad's satisfying narratives, Encyclopedia Brown stories aren't classic stories. They're really sort of like epigrams, they're riddles that he solves and the ending is satisfying. Yes, he has triumphed, but really it's satisfying because it's like, "Oh, I get it." And I loved that feeling. I think it's the same feeling that, I saw with my dad when he would tell his sort of moralistic tales. And then in second grade and third grade, I got really into Roald Dahl. So I was always the kind of reader who I didn't read. I still read very slowly. When the seventh Harry Potter book came out and my wife and I got it together and we had to we were reading it at the same time, she would finish a page like a full minute before I would. And she would just like tap her knee and like look off into the distance until I finished. So I've always been a slow reader. But I've always also been a reader who, once I find the thing I love, I like just die. So all the Encyclopedia Brown books moved on to all the Roald Dahl books.

Adam Gidwitz: I probably hit most of the Matt Christopher books at that time. And even today I am less broadly read than I wish I were. But I've read nearly all of the John le Carré books, especially before the Cold War ended. And I could tell you really deeply how he does what he does, because that's the kind of reader I am. I sort of get lost in one person's technique and it just makes me very satisfied.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Jacqueline Woodson has that really nice TED talk about close reading. My son is more like super, super fast and just read through everything, everything he just consumed. But my daughter, they're very different. But I see that... It's cool for him. He has such a wide breadth of what he's read. But for her, she's like deep, slow into a book, you know?

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah. And it really, it takes all types. There's not one type that's better to be a writer or a reader or a thinker. I mean, really, like the people who have read everything are so valuable. And then those who have like read it very closely, also valuable. So it's all good. If you're reading, it's all good.

[music]

Adam Gidwitz: The BFG expressed a wish to learn how to speak properly. And Sophie herself, who loved him as she would a father, volunteered to give him lessons every day. She even taught him how to spell and to write sentences, and he turned out to be a splendid, intelligent pupil. In his spare time, he read books, he became a tremendous reader. He read all of Charles Dickens, whom he no longer called Dahl's chickens, and all of Shakespeare and literally thousands of other books. He also started to write essays about his own past life. When Sophie read some of them, she said, "These are very good. I think perhaps one day you could become a real writer." "Oh, I would love that," cried the BFG. "Do you think I could?" "I know you could," Sophie said. "Why don't you start by writing a book about you and me?"

Adam Gidwitz: "Very well," the BFG said. "I'll give it a try." So he did. He worked hard on it. And in the end, he completed it. Rather shyly, he showed it to the Queen. The Queen read it aloud to her grandchildren. Then the Queen said, "I think we ought to get this book printed properly and published so that other children can read it." This was arranged, but because the BFG was a very modest giant, he wouldn't put his own name on it. He used somebody else's name instead. But where, you might ask, is this book that the BFG wrote? It's right here. You've just finished reading it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Roald Dahl, despite his complicated legacy, is one of children's literature's most imaginative and prolific writers. The title character of his 1982 novel, The BFG, is a kind, sensitive giant, unhappily surrounded by his cruel, child-eating brethren. Unable to protect the little ones from his peers, the BFG secretly uses his magic to send them fantastical dreams, providing the children with moments of joy, escape, and adventure. It's not a stretch to see why Dahl would end the story by pulling back the curtain to say that he and the BFG were, in fact, the same character. And that reveal is something that Adam Gidwitz can't get enough of.

Adam Gidwitz: That makes me tear up every time. I think the idea of like the meta-fictional stuff, and also just that he became a writer, despite not expecting to be a writer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Do you remember when you read it?

Adam Gidwitz: It would have been the second or third or fourth grade. And I remember, I think I claimed to have read it 13 times. I'm sure I didn't, but that's certainly what I told everyone. It probably just meant I read it one and a half times and felt like I loved it so much.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Why did you love it so much? What do you think it's like brought forward into who you are now?

Adam Gidwitz: I mean, I feel this way both about The BFG and my favorite of all Roald Dahl books, and in fact, my favorite book ever written for children, Matilda.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Me too.

Adam Gidwitz: You too?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: That's like my book, yeah.

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah, Matilda is my favorite book. It's classic and we might even call it cliche, but Matilda in particular is about a kid who is brilliant and nobody recognizes it. And through courage and a little bit of naughtiness and some love from a few key people, her brilliance comes out in the world and it's pretty powerful and she uses it to do good things. I mean, maybe I could be telling the story of Harry Potter, but let's be honest, Matilda is way more interesting than Harry Potter is. I mean, as a character, she's way naughtier.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: You said that you cry every time when you read the end of that book. Do you have memories of reading it as a kid?

Adam Gidwitz: What I do remember is I remember reading Kate DiCamillo's The Tiger Rising aloud to my fifth graders when I was teaching fifth-grade language arts. And just by the end, it was like the end of the school year, and as anyone who's taught knows, kids are done learning, but teachers are really done teaching. By May we're like, "Get me out of here." So the only thing that I wanted to do was sit and just read with these kids a wonderful piece of literature. And reading those last chapters of The Tiger Rising by Kate DiCamillo, I was just weeping. There was snot coming out of my nose, tears streaming down my face and my fifth graders were like, "Are you crying?" And I was like, "Yes," you know. So yeah, I'm a crier when I read books. I really am.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: She's actually the last person I interviewed. And it's funny because I'm like writing the script for that now. And I'm like, "I think we need to talk about how much everybody cries when they're with Kate DiCamillo." And like, she just like elicits tears, the woman. It's like they're happy tears, but they're still crying.

[music]

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah, she talking about knowing how to land a story. She knows how to land a story.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Perhaps one of the most unique and attractive qualities in Adam's work is his personal voice, his delivery and the way he speaks to his readers makes his stories fun, accessible and personal.

Adam Gidwitz: What I realized was that I'm most effective as a writer when I'm just talking to my reader. So I just I try to do that. I just talk to my reader and write down what I'm talking about, what I would be telling them if they were sitting in front of me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: This ability is what really sparked his writing and gained Adam his first bits of praise. But it still took trial and error before he came to the realization that his voice is what made his work special. Adam's career and writing began while he was working as a teacher. He had been giving a lesson to some of his younger students about ancient Egypt, and decided to write a story for his class chapter by chapter to help teach the material. The response was incredible, and it inspired Adam to quit his job and work on turning that story into a real novel, a novel with a very specific voice in mind. Only it wasn't his voice.

Adam Gidwitz: My thought was, I think this book could be great. I think it could be Newbery-worthy. So I'm going to rewrite it so it sounds like Johnny Tremain. Like that was like my model. I sent it to an agent who I had met actually through that school. She told me it was bad. And that if I wanted to start on a different project, she wouldn't blame me, which was adult code for throwing it in the trashcan.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Despite the hurdle, he was not discouraged. Adam took a job as a substitute librarian while he reassessed. There he had a breakthrough, one that makes a lot of sense for a writer who grew up hating to write, but loving to narrate stories in his driveway. During library time, Adam started reading Grimm's fairy tales aloud to children, taking license to add warnings, ad lib and humor to make it palatable for young audiences. And the kids loved it.

Adam Gidwitz: I opened it up to a story called Faithful Johannes. And in the story, Faithful Johannes, two children get their heads cut off by their parents. They get put back on again, so they're fine. But I read that and I was like, that's interesting. Can I read this to second-graders? Will I get fired? By the end of the story, some of them were traumatized, but a bunch of them really loved it. And this little girl came up to me and I'll never forget it. She walked up to me and she stuck her finger in my face and she said, "That was good." And I said, "What?" And she said, "You should make that into a book."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: That story would become the first chapter of Adam's best-selling book, A Tale Dark and Grimm.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Looking back at his days making up stories while playing basketball in his driveway, it's clear that Adam was always a gifted storyteller. But the journey to actually getting his words on paper was a circuitous one because oral storytelling wasn't a part of his formal or writing education. I wanted to learn more about the lessons he's learned through that process and the importance he places on oral storytelling in the classroom.

Adam Gidwitz: I know there are some curricula out there that focus on the oral tradition, but I agree. We focus a lot on writers workshops, but the most primal way that we get stories is orally. And the most primal way that we have shared stories through our evolutionary history is orally. And I think there's so much to be learned from public speaking to empathy to a host of other things that we could learn by practicing and studying the oral tradition. I also think that when you take anyone who has studied Shakespeare knows that when you memorize some of Shakespeare, it goes deep inside of you and then it comes at random times, right? If you're acting in a Shakespeare play, then you have been the annoying person who like interrupts a dinner party to like quote Shakespeare in response to what somebody said, because it applies in almost every situation. And so taking literature into your body like that is really powerful. And for younger children, even for older children, these traditional stories are a really powerful way of doing that so that we can take the deep wisdom and mythology, the emotional working through that these stories do, and we can embody them ourselves.

Adam Gidwitz: And then it teaches empathy because when you're telling a story, the best storytellers are deeply empathic with their audience. We watch our audience, we respond to our audience, we listen to our audience, and we shape the way we tell the story, maybe the details of the story or maybe just the delivery of the story to the responses of our audience. And that's a real exercise in empathy.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Staying true to his voice was a crucial step for Adam and his journey as a writer, but there's more to it than just how he says things. He's also spent a significant amount of his life trying to find truth in what he says.

Adam Gidwitz: When I went to college, I thought I was going to be a philosophy major. And then I took a philosophy class and I was, not only did I hate it, but I was also terrible at it. I didn't understand it. I was like, "Okay, Plato says some cool things, but it's 98% wrong. What are we debating exactly? It's just the answer is no to all of these things he says." I just never understood the point of it, so I did terribly in those classes. And then I shifted to religion because, again, I was just looking for fundamental truths. But the religion classes just talked about the history of religions, and those were clearly, I mean, I am myself religious, but the history of religion is just a series of lies and wars. So that was not where I was going to find truth. And then I took an English class and essentially the structure was this book is really good. You should read it. And then I would read it and I would come back and be like, not only was it really good, but the observations in it, in Jane Austen's Persuasion, for example, felt so deep and true.

Adam Gidwitz: I think not like the grand statements, right? I think what I had learned by that point in college and what I continue to believe is that the world is so complex. No theory that anyone has can be accurate because the only accurate model of the world is the world, right? There's too many complexities. Everybody is too unique. There's no predictive capability at all. That's why you can't tell the future. And so what literature does is it catalogs the unique and particular truths of the world. And a really great writer, a Jane Austen, a Chekhov, a Kate DiCamillo will take one of those truths and reveal it to you in a narrative way that's just so deeply satisfying. And at the end, you're just sitting there looking at something that feels truer than anything that Plato wrote, than anything in any of those religion classes that I took. And so what I try to do now, some of my books, I try to do sort of psychological truths like in A Tale Dark and Grimm. And some of the books are a little bit more individual and unique. The Inquisitor's Tale, the thing that I love most about that book are the characters in it and not even the main characters like some of the random knights or like Abbot Hubert, who's a bad guy, but why he's a bad guy. Trying to document the truths that I see in the world is among the most satisfying things that I do as a writer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Do you think that, I think especially when it comes to kids, although I know there are many kids that like nonfiction writing, but do you think that it is like easier, more effective to communicate those truths through fiction than maybe the alternative?

Adam Gidwitz: I think for a lot of kids, certainly it was for me. Everybody loves a story. Even kids who love nonfiction love a story. And I love nonfiction stories, by the way, like Steve Sheinkin's books are just so great because he tells unbelievable nonfiction stories. And for adults, Ben MacIntyre is a similar way. When you're reading a story and there's a character that feels really true, especially as a child, I can remember many instances of this where a character felt so vivid to me, but utterly new. I didn't know anybody like that and I didn't quite understand their behavior. And then later in life, I would come across people and be like, oh, that person is just this character. And I understood the world so much better. I felt like a worldly person, especially after college and having read all those books. I felt like a worldly person without having had to go anywhere because I inhabited other people's lives. I think I have a T-shirt. I don't know where the quote is from, but I read a lot, not because I don't have a life, but because I have many. Reading The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, you just like, "Oh, I know people in a deep way that I never would have had I not read these books."

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Adam's Faith in Literature as a Vehicle for Truth is something his newest novel will put to the test. In it, he's chosen one of recent history's darkest settings to illuminate the complex humanity of characters we often label as simply evil. The story follows a young boy who manages to get back into Germany as a spy and is tasked with infiltrating the radio broadcast center of Nazi Germany.

Adam Gidwitz: You may know that Nazi Germany had a very robust radio propaganda program. They used radio much the way that Trump used social media to galvanize their movements. Max, my main character, his task is to infiltrate their programming and understand how they got a nation, the nation that had been known around the world as the nation of thinkers and poets, that was Germany's like tagline before the Nazis. How they got the nation of thinkers and poets to commit themselves to lies. That's what I think is the salient feature of Nazi Germany is that Hitler was up there telling just blatant lies. And a lot of people knew that they were lies. And then many more people should have known they were lies. And yet he got a nation to wholeheartedly enthusiastically commit themselves to these lies to die in battle for them. How? That's the question of the book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: In the story, Max meets many Nazis and works to uncover what motivates each one. Terrifyingly, he finds the answers are endless.

Adam Gidwitz: There was a really amazing study done in the 1970s of people in France who had collaborated with the Nazis. And the researcher was trying to figure out what unified their collaboration, their motivation for collaborating with the Nazis. And his conclusion was, there were as many reasons to collaborate with the Nazis as there were collaborators. We all have things that we want out of this world, out of this life. And we are willing to lie to each other and to ourselves in order to get those things.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: It's so interesting to me because you have these different entry points in your writing. This feels like a more monumental type book for you, It's kind of like a capstone in a way, although it won't be because you got more coming.

[laughter]

Adam Gidwitz: I hope not.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: But does it feel that way to you? Like you've been kind of waiting to write this one?

Adam Gidwitz: Yeah. The Inquisitor's Tale felt like, I wrote that book between really 2012 and 2016 when it came out. It felt like I put everything that I knew about the world into that book. And to me, my ambition for this book is that this is my sort of next installment of the Inquisitor's Tale type books. Everything that I've learned, certainly since 2016, is in this book in one way or another.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah, I'm personally really, I just actually, my son's about to have his bar mitzvah in about a month. And so I took him to the Holocaust Museum this week. When we very first walked in, the first commentary he made to me was like, "God, so many people." And I said, "Yeah, 12 million." And he was like, "No, I mean, yes, a lot of people died." But he said, "It was just so many people who went along with this." And he's looking at all the floor about the propaganda and everything. And that was, I thought, that is what shocked him most at the beginning, certainly. But it really speaks to what you're talking about. It's just, that's the big question, not just how we can do this to one another. Like you said, how we can force ourselves to believe a lie or...

Adam Gidwitz: He's a smart boy. And I agree. I think one of the things, this book will probably be controversial. I was very worried about Inquisitor's Tale before it came out about it offending people. And in fact, I did lose some friends over it, which makes me sad. Some very Orthodox Catholics didn't like it, which surprises me because the heroes of the book are pretty much all Catholic.

Adam Gidwitz: And they support God and all that stuff. But some people probably won't like Operation Kobold also for the reason that I depict the Nazis as humans. And a lot of books and movies, they're depicted as monsters. And what they did was monstrous, as bad, worse than anything that's ever been done, arguably. But it's important to me that we depict them as humans because we have to understand how humans could do monstrous things. And we have to be aware and vigilant because there are those impulses to do monstrous things in our neighbors, in our compatriots, in our families, even in ourselves. And if we see them as Nazis as totally foreign and alien to us, then we won't recognize it when we start walking down their path.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: If one of your stories, anything or adapted into a show, any other of the story, who do you want to be?

[laughter]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Who do you want to play? Don't worry about like who they are, if you look like them, etcetera. But like, who do you want to be?

Adam Gidwitz: I'll tell you the truth. Ever since The Tale Dark and Grimm came out, I wanted to, this is going to sound terrible, but I wanted to play the devil.

[laughter]

Adam Gidwitz: Because he is not the real devil, just for all of you out there who are worried about that. He is very much a character and a caricature of the devil. But the way that I wrote him was, I just felt like delicious. He was like sinister and urbane and funny. And so when A Tale Dark and Grimm got turned into a Netflix show, I have to be honest, I was very quietly and privately lobbying to play the devil myself. And then they got Adam Lambert to play the devil. And he has the most amazing voice-acting ability of anyone I've ever heard, I have to say. And his devil is so much better than anything I could have ever done. So I still want to be the devil, but I never will be because Adam Lambert is just more talented than I am. That's all there is to it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Damn, Adam Lambert.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Adam's career began with fairy tales. And now for his challenge, Grimly Ever After, he's bringing those stories to us.

Adam Gidwitz: I've chosen a handful of fairy tales, original Grimm fairy tales, some of which you may know, and many of which you probably don't know. And I'd like you to read those and then you can listen to an adaptation of that fairy tale on my podcast, Grimm, Grimmer Grimmest. That's true for the first half of them. And then the second half of them, you could read that original fairy tale and then read the way that I adapted it for my book, A Tale Dark and Grimm or In a Glass Grimly. And I think it might be interesting to do that and look at how in some ways I adapted them very faithfully. But you'll also see I make some serious changes. Sometimes the changes are political. There are some like really retrograde worldviews in the Grimm fairy tales. And I think we can do a lot better today. And a lot of times the changes are stylistic. I'll keep the details. I'll even keep the structure, but I'll change the language and the pacing so that they appeal to today's readers. So that's my reading challenge. And I hope you read some interesting things, listen to some fun things and learn and enjoy.

Adam Gidwitz: And this episode's Beanstack Featured Librarian is Jessica Juarez.

Jessica Juarez: My name is Jessica Juarez. I am the district librarian in Robstown ISD and I am housed at the high school. My secret sauce to get kids excited about reading, honestly, I don't really think there's a one size fits all for students, especially high school students who are so busy with all sorts of things. I try to keep my selection of books as up-to-date as possible. And then really it's just promote, promote, promote. I think one of the most successful ways to get them to pick up a book and read is posting the student-written book reviews on the wall. Because when they see book reviews written by their peers and their peers have read and loved it, they're going to be more likely to check that out.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: This has been The Reading Culture. You've been listening to my conversation with Adam Gidwitz. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey. And currently, I'm reading There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy and Spirit Hunters by Ellen Oh. If you enjoyed today's show, please show some love and rate, subscribe and share The Reading Culture among your friends and networks.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, check out all of our resources at beanstack.com. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script-edited by Josiah Lamberto Eakin. We'll be back in two weeks with another episode. Thanks for joining and keep reading.

[music]